Previously I have blogged (on the NHSX website) about the design of a minimally-viable remote monitoring service in rheumatology medicine. The meaningful remote clinician-patient relationships which have developed through regular interactions with the service have been reliant upon TRUST and the sharing of patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) data outside of hospital-based care. Patient engagement and trust in the service remains high, with an accelerated uptake of the service during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is still much to learn about what influences human interactions with the service. A Theory of Change (ToC) model has helped to make sense of the behaviours and anticipated actions taken by patients using the remote monitoring service across the South East London Integrated Care System.

What is ‘Theory of Change’?

A Theory of Change (ToC) model diagrammatically describes a set of pre-conditions and rationales connecting a sequence of events which are expected to lead to a desired outcome or achievement of a goal. The central idea in ToC thinking is to make assumptions explicit and describe the different pathways that might lead to change. ‘If we do X then Y will change because….’

The assumptions made about the remote monitoring service were as follows:

- #assumption1 – By offering a flexible means of communication for patients there will be a positive impact on care.

- #assumption2 – By framing the importance of PROMs in rheumatology care, patients will want to use the service.

Meet Patient Joseph (whose feedback below is real although Joseph is not their real name).

I love it. It’s so, so much more useful than any of the private ‘monitor your health’ apps because 1. It’s simple 2. The graph is ace 3. It goes onto my file 4. I’m working in collaboration with my healthcare team.

Below, one-by-one, each of Joseph’s individual points of feedback about their experience of the remote monitoring service is taken and mapped onto the Theory of Change model to illustrate the value of a Theory of Change approach in testing these assumptions about the remote monitoring service. Where the feedback indicates that an assumption has been met, this is indicated by the addition of the individual assumption hashtag.

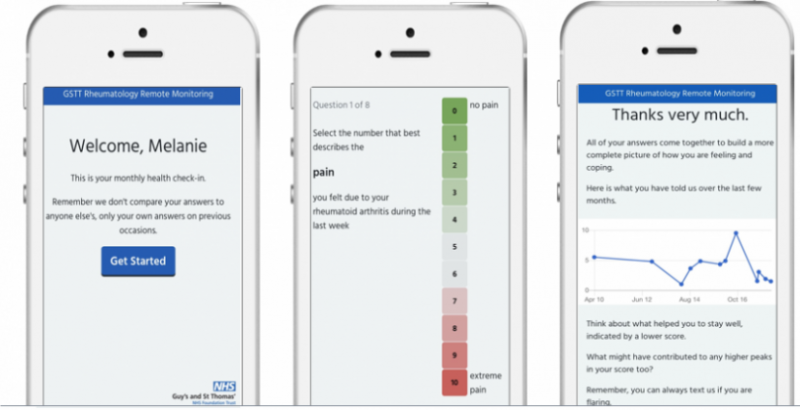

Feedback point 1. Joseph said, ‘It’s simple’. An intentional design function of the remote monitoring service was to simulate 2-way SMS communication which mimics familiar social interactions thereby making it more likely for a patient to use the service. #assumption1 #assumption2

Figure 1a. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 1 testing #assumption1 and #assumption2 (Click to enlarge)

Figure 1b. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 1 testing #assumption1 and #assumption2 (Excerpt)

Feedback point 2. Joseph said, ‘The graph is ace’. A graph displaying responses over previous months was a prioritised feature through user research. The proposition was to provide patients with immediate and sequential feedback about their own data, hypothesised to contribute to sustained patient engagement. #assumption1 assumption2

Figure 2a. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 2 testing #assumption1 and #assumption2 (Excerpt)

Figure 2b. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 2 testing #assumption1 and #assumption2 (Click to enlarge)

Figure 2c. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 2 testing #assumption1 and #assumption2 (Excerpt)

Feedback point 3. Joseph said, ‘It goes onto my file’. Here the assumption is that the exchange of meaningful data has a positive impact on care. #assumption2

Figure 3b. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 3 testing #assumption2 (Excerpt)

Feedback point 4. Joseph said, ‘I’m working in collaboration with my healthcare team’. This behaviour supports the wider goal of personalised care by making potential use of shared decision-making and patient-initiated follow-up more confidently informed by better data. #assumption2

Figure 4b. Patient Joseph’s feedback point 4 testing #assumption2 (Excerpt)

Transforming Rheumatology

In line with the NHS Long-Term Plan, the goal to transform rheumatology out-patient services beyond the traditional model of arbitrary face-to-face appointment scheduling towards a model of remote data sharing at a time of the patient’s choosing has the potential to be incrementally mapped using Theory of Change modelling. The use of ‘real-world’ user feedback and survey data can help to iterate a Theory of Change model and inform the co-design of remote services which better understand the motivation that drives usage and which possess the deliverable qualities of usability and sustainability.

Usability

Usability is about simplicity. If something is simple to use, it takes less time to learn. It will perform as well next time and is a good experience for the user. When the design lens is on usability it puts the patients at the heart of the technology and helps to drive quality in digital healthcare.

Sustainability

Sustainability as a dimension of service design brings into focus the social, environmental and economic considerations of receiving care remotely. Better understanding of the incremental health behaviour change required to sustain engagement with remote care is needed to optimise benefits realisation.

Technology

The term ‘new normal’ has been used to describe a period of rapid adoption of digital practices and processes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatology medicine has seen a significant shift towards delivery of remote consultations (PDF file) and the remote capture of electronic patient-reported outcomes with technology the key enabler. The beneficial change has been the potential for interplay with virtual consultations and remote monitoring as enablers in #makingeveryvirtualcontactcount.

The application of an iterative Theory of Change approach has helped to focus our attention on understanding human behaviour before the technology. An appreciation of the behaviour change likely to contribute to meaningful interaction is key to the building blocks of TRUST when scaling digitally-enabled, data-driven remote care across rheumatology services beyond COVID-19.