With every workshop, event or meeting, I squeezed in at least one opportunity to ask the host, presenter or the audience this question. My Topol Digital Fellowship project was to develop a framework of digital competencies for a specific group of healthcare workers, Allied Health Professionals. In doing this work, I cultivated a need to understand what level of digital competence is required for the average physiotherapist, nurse or hospital administrator. Hopefully, if you read on, I will be able to answer this question.

Free basics

In some places in the world, such as Brazil, daily news is largely hidden behind a paywall, making access to information limited for large groups of the population. Although mobile data is cheap or even free in Brazil, in order to find out what is happening across the world, people have to pay for access to information. However, via instant message, they are freeto share screenshots of headlines taken from those who do have access to news websites. As such, many of the population develop their view of the realities of the world based upon limited thumbnails of fact, devoid of context or elaboration. This can lead to an incomplete, somewhat superficial understanding of important topics which require their attention. This, oddly, is similar to what I have seen across much of the workforce, when we consider digital technology in healthcare practice.

Most healthcare workers may have a deep understanding of pockets of topical information, but amongst many the broader spectrum of digital competency remains limited to a thumbnail of what they have time to glean from independent research or postgraduate training. This is partly because of the expanse of everything digital technology encapsulates. But it is within the area between the photographs of headlines that true competency (that is, knowledge and abilities) lies. The advancement of technological innovation in practice depends upon the workforce moving beyond the memeification of digital knowledge, to a more substantial degree of competence in relevant areas to each professional.

An example – Allied Health Professionals

Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) are the third largest clinical work force group in health and social care (1), with 223,991 individuals registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (or national bodies) in the UK in 2020 (2–3). The variety of professions (of which there are 14) means the group is largely heterogeneous in relation to its knowledge, skills and professional roles. The 14 AHPs are listed below:

- Art Therapists

- Dietitians

- Drama Therapists

- Occupational Therapists

- Operating Department Practitioners

- Orthoptists

- Orthotists/ Prosthetists

- Osteopaths

- Music Therapists

- Paramedics

- Physiotherapists

- Podiatrists/ Chiropodists

- Radiographers (Diagnostic & Therapeutic)

- Speech and Language Therapists

This broad spectrum of clinical practice means that as a cohort AHPs may be a suitable model to reflect the heterogeneity between other medical and healthcare professional groups. That is to say, understanding what digital literacy is for this group, may provide some transferability to other groups (e.g. midwives, nurses, doctors, etc.)

But what do we mean by digital literacy?

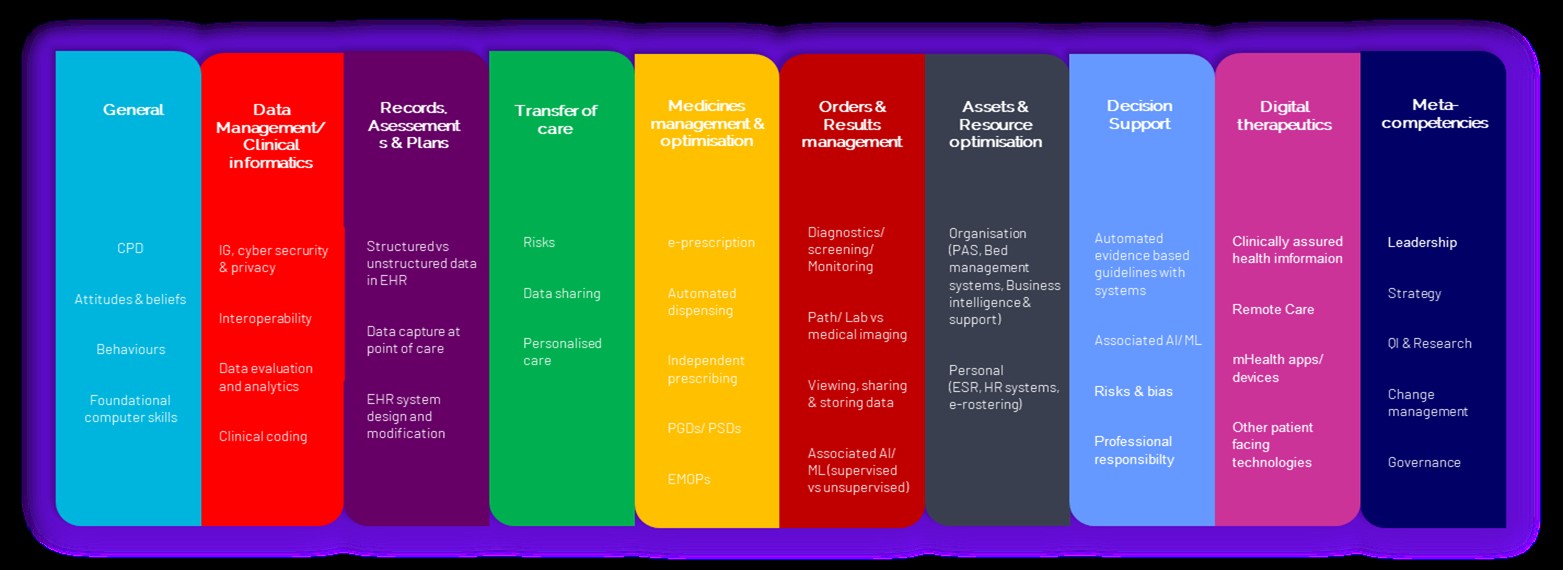

Health Education England define it as “the capabilities that fit someone for living, learning, working, participating and thriving in a digital society” (4). For our purposes, we should ask what is the required level of confidence, motivation and competence (knowledge and skills) which is required for the healthcare worker in order to learn, work, participate and thrive within their specific job role? My digital framework illustrated below (and which can be clicked to enlarge) outlines areas of competence which are important to the diversity of AHPs.

Figure 1. Summary illustration of the AHP Digital Competency Framework. (Click to enlarge)

Figure 1. Summary illustration of the AHP Digital Competency Framework. (Click to enlarge)

A model of digital competence

The AHP digital framework consists of 124 competencies across 10 domains, which has been formulated through a Delphi study of an expert panel representing all AHP roles. Whilst this framework is specifically derived for the needs of these selected professions, it is likely to identify themes which all healthcare workers can consider when thinking about their own digital development needs.

Non-clinical competence

One example of a transferable area across professions is the ‘General’ domain. Competencies in this group cover foundational understanding of the systems and devices the individual has to use on a daily basis, as well as their attitudes and behaviours to facilitate engagement with technology for themselves and others. The average healthcare worker therefore needs to be aware of the digital aspects of the environment they work in, and be reflective upon their own feelings and confidence with technology. Similarly, the ‘Metacompetency’ domain contains competencies which cover transferable elements of practice, such as knowledge and skills related to the use of digital in research and quality improvement, and the leadership skills required to build strategy towards digital transformation. All of these competency areas are shown to be very relevant to all AHPs and a good starting point for those interested in improving their digital competence.

Key topic areas

Some domain areas can be themed and are important for healthcare workers to have a deeper understanding of, even if they are applied in different ways. I will summarise some of these below:

Data and informatics

The understanding and use of data in healthcare practice is becoming more and more of a pertinent topic. For the average healthcare worker, this can be as simple as identifying what type of data they are using on a day-to-day basis, whether it is structured or unstructured, and what the differences are between the two. An understanding of how patient data can be collected for individuals and larger groups to aid clinical care is an extension of this competency. Of course, an essential area for all staff to gain knowledge in is the management of data privacy, cyber security and information governance. Some of this may be compulsory and met by attending mandatory training. However, individuals should also be aware of their local organisation’s policies around how to protect patient data. This could be as simple as being able to recognise suspicious phishing emails or knowing how to construct a sufficiently strong password.

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

There is a lot to learn about AI in healthcare, much of which does not aid the average healthcare worker in practice. It is an exciting and interesting topic, but what information is sufficiently relevant to spend time learning? For AHPs, machine learning and AI raises its head when developing knowledge and skills around clinical decision support systems (CDSS) in practice. CDSSs aid patient care by collating information and providing targeted knowledge to augment a medical decision. Such systems will increasingly underpin results reporting or be embedded into EHR systems for use in practice. Such tools include risk alert systems in intensive care, outpatient patient triage systems, or automated radiology image analysis and reporting.

Machine learning (ML) is used in these examples to collate and analyse the data by which decisions are made, and there are principles which are helpful for all healthcare staff to understand. Namely the methods of ML to classify or predict based upon the data it is fed. Computers can be used to collect and look at lots of patient data to identify patterns. For example, we can take a month’s worth of images from patients presenting for an x-ray after suffering an acute ankle injury, and an appropriately trained system can use the radiograph images and classify those which do, and do not, show a fracture. Alternatively, machine learning could be used to analyse the data of a group of patients and predict the probability of them developing x disease. For example, a cardiology clinic could combine and analyse all of the ECGs undertaken over the last six months to identify patterns consistent with risk of heart attack. Each individual patient’s history and current status can then be evaluated against that pattern to predict their clinical risk. The increasing use of wearable devices to constantly measure heart function provides more data to enhance such algorithms. Knowing how machine learning works to classify and predict, will allow all healthcare workers to consider whether or not it could be used to tackle such problems in their work.

Digital care provision

A final transferable area for all healthcare workers to consider is how digital technology is used in the practice of their specific area, and the principles which underpin this practice. For AHPs, this domain includes the understanding and use of mobile applications to augment care pathways, the ability to capture patient data with digital devices and the provision of care remotely using digital technology. Every area of health and care will have its own degree of how relevant these technologies are, but understanding the reasons for these tools to optimise accessibility is important. All healthcare workers should understand the potential benefits of technology and be able to evaluate whether it is appropriate in their own specific areas of practice. Being able to offer video-based consultations, or to enhance traditional pathways through remote monitoring, are likely to be highly transferable services and as a baseline should be considered for all staff.

So, how much ‘digital’ is enough?

In this blog, I have tried to highlight key areas which seem more widely relevant to all healthcare staff. Each person working in healthcare would do well to consider some of the areas highlighted above in order to self-evaluate their current knowledge and skills, as well as plan their future development. Thus, the collective knowledge base of all staff together will add context, enhance its depth and become more defined to their specific environment. Digital transformation of healthcare practices will be guided by the needs of both the individual AND the needs of their professional role. When taken together, every healthcare worker can help ensure that the changes we make towards technological innovation are appropriately focused towards the specific needs of the service, and ultimately the people who matter most – our patients.